It seems that crime is on the rise in the area where I live, and in my “gated” (when they actually close) apartment complex. I’m going out of town for a while to visit family, and was a bit wary of leaving my apartment - and all of my posessions, and most importantly my cats, unattended for too long. I’m having some family in the area check on the cats every few days, but that doesn’t do a lot for my peace of mind in a complex that’s had a few break-ins this year.

I’ve played around on previous trips with with motion, a motion-activated video recording tool, and a Logitech C310 webcam, but with four cats, it’s far from a tool to detect a human in my apartment. So, the weekend before my trip, I decided to do some tinkering.

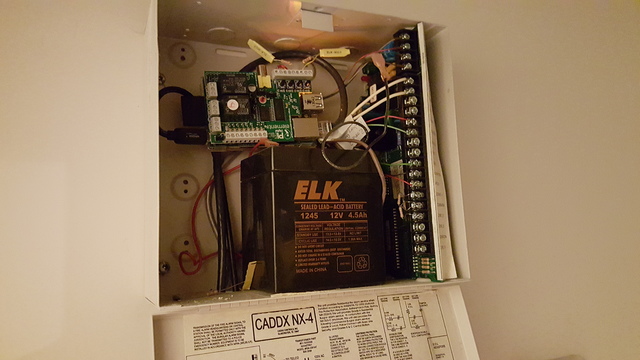

There’s an “alarm system” control panel next to the entry to my apartment, but it appears to be a no-name system that probably cost $20 and doesn’t actually do anything other than sound a chime when the door opens. I turned it off the day I moved in, and hadn’t given it a second thought since. However, it occurred to me that the useless panel next to the washing machine probably had magnetic contact switches for the doors. Sure enough, after a few minutes with a multimeter, I found that both the entry door and the sliding balcony door have normally-closed magnetic contacts wired back to the panel. After thinking over the options for a few minutes, I remembered that I had a Raspberry Pi (the original) sitting unused under my TV, and a PiFace I/O card that I’d never used.

After about an hour of connecting some wires and playing around with the wonderfully-simple pifacedigitalio Python package available on PyPi, I was able to successfully read inputs for when either door was open. I figured that this would provide the perfect squelch for motion recording from the webcam, as the cats aren’t able to operate the deadbolt on my front door (I had to replace all of the interior door handles with cat-proof models).

The system that I’ve come up with is rather rough around the edges… to put it lightly. It’s pretty obvious that it was written in a few days, and at this point, it’s not really intended to be used by anyone who doesn’t have a good understanding of the components (and Python). But I’m hoping that someone else might find it interesting, or perhaps improve on it. It’s not terribly robust, but it seems to be working acceptably well for my needs.

Components

The system is split into a number of components, with some of them running on the Raspberry Pi and some on my desktop computer.

The Pi is running my piface-webhooks project (everything needed to set it up on Raspbian or OSMC is available in the repo), which is made up of two Python services:

- piface-listener Is the code that actually polls the PiFace inputs. When the state of an input changes, it writes out

a file (under

/var/spool/piface-webhooksby default) with the input number, state, and timestamp. - piface-worker Polls this directory for files; when one is found, it takes some action and then removes the file. The

current actions are sending an HTTP webhook, sending a message via Pushover, and sending an email

via Gmail. I currently use all of these, mainly for redudnancy. The webhook feature is used to POST data to

motion_piface_handler.py, a Flask app running on my desktop.

My desktop computer is the heart of the system, handling the webcam and most of the “alarm” logic:

- motion monitors the webcam feed for motion above a certain number of pixels. When motion is detected, it saves both JPEG images and AVI files to disk, logs the event in a MySQL database, and executes a Python script. It also saves a snapshot from the webcam every 30 seconds.

- s3sync_inotify.py is a quick Python script I wrote that

uses Linux inotify to monitor

motion‘s output directory for new files (only when they’ve been closed, and are finished being written) and syncs them to an S3 bucket set up for static website hosting. It also generates anindex.htmlfile for the bucket, with links to all uploaded files. At startup, any files that aren’t yet synced are uploaded, so it should handle crashes relatively well. - handle_motion.py is the command executed by

motionwhen an event is detected; it POSTs data tomotion_piface_handler.py. - motion_piface_handler.py is the heart of the system, explained below.

motion_piface_handler.py - Pulling it all together

Webhooks from both the Raspberry Pi door sensor and motion‘s command execution go to a Python Flask app

running on my desktop. This app accepts the incoming data, and also connects to the MySQL database used by Motion. When a POST from

piface-worker comes in showing that a door has been opened, it adds a record to the MySQL database with information on the input

pin (which door) and state (open/closed), and timestamp.

When a POST comes in from handle_motion.py, the command executed by motion when a file is written, the app checks to see if

a door has been opened in the past few minutes. If not, the event is ignored (and logged, of course). However, if a door has been

opened, the real fun starts. First, the database is queried for the last time a notification was sent out. If one has been sent

in the past few minutes, the current event is ignored (and a rate-limiting message is logged). If it hasn’t sent out a message

recently, the database is queried for the last door event (which door, and if it was opened or closed) as well as the last AVI

and last five JPEGs saved by motion. This information is all formatted into a message and sent to my GMail account, and a

shortened version (with just the door event information, and that motion was detected) is sent to my phone via Pushover, with

the highest priority and a custom notification sound.

So far - at least as far as taking my dogs out is concerned - it appears to be working relatively well. There’s a bit of latency in the S3 uploads, especially when AVIs are written, so the files linked in the notification emails may not be uploaded before the message goes out. That’s a bit annying, but something that I think I can live with.

The use of disk queueing probably isn’t the best, especially with the Pi’s SD card, but I wanted something that was simple and didn’t introduce any additional service dependencies. Each of the components runs as a systemd service, configured to always restart, so it should tolerate internal failures relatively well. The Python code has a lot of bare excepts; I’m not sure this was the right way to approach it, but my initial theory was that in the event of an error, I’m more concerned about keeping the system running than getting an individual message through. The point of the system is to let me know if my home - and more importantly, my four-legged children - are in danger. I figured that I’d rather get a delayed notification than none at all.

Results

After two weeks away, the system worked quite well. It triggered correctly, and quickly, when my family came to check on the cats. On average, it took about 3-5 seconds for me to receive the PushOver and GMail notifications for a door open event, and about 30 seconds for an alarm (motion after door state change) event.

However, I did have a few issues:

- Late one night, I got a door open alert when I hadn’t been expecting anyone. After about half an hour of panic checking the webcam feed and watching the logs remotely, I determined that it was a false positive. All was well, there wasn’t any sign of anyone in the apartment, the cats were all wandering (or lounging) around as normal, and the door never registered as closed. A day or two later, the door registered as closing. I’m not sure if this was an issue with the door sensor triggering because of wind or vibration, or an issue with the PiFace itself having internal issues reading an input over such a long time, or something with induced current in the long unshielded sensor wire in the wall (and possibly compounded by my naive debounce logic).

- Having

motionstore everything in one directory, and thens3sync_inotify.pysync that to S3 and create anindex.htmlfile was a bad idea.motionwas triggered quite often by the cats; after about a week away, I had ~10GB of photos and videos in the S3 bucket, and theindex.htmlfile was over 7MB. Not only did the index page take a painfully long amount of time to load, but generation of it introduced enough latency in the upload process thats3sync_inotify.pyended up missing a large number of files.

Next Steps

I’m not sure if I’ll do much more work on this - we don’t travel often - but if I do, the next things that I want to tackle are:

- Queueing of outgoing messages, so that network outages won’t result in completely-lost communication.

- Some sort of heartbeat - ideally to an off-premesis system, such as my EC2 instance - from every process involved, to confirm that all of the components (a) are running correctly, and (b) have connectivity.

- Modify the

motionoutput directory structure ands3sync_inotify.pyto write into per-day (or per-hour) directories and writeindex.htmlfiles for each of them. - See if there’s a straightforward way to use systemd’s sd_notify from Python, to build a watchdog into the processes and have systemd restart them if they hang.

- Packaging this all together into one or more real repositories, so maybe it can be used by others.

- Cleaning up

handle_motion.pyandmotion_piface_handler.pyand releasing them along with everything else.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus